Agriculture is often suggested as one of the main drivers of pollinator loss by causing damages to their habitats and resources. But we can’t stop our food production and for this production we need pollinators. Both have to continue side by side. A good management of farming area can resolve this issue, providing both good agricultural outputs and good habitat for pollinators.

- The limestone paving is one of the key habitats in the Burren region. Image credit: Marie Carco.

The Burren region is situated on the seaboard in the west of Ireland, and is a successful example economically viable agriculture for farmers while also having benefits for biodiversity. This limestone landscape has a really rich flora (more than 600 of Ireland’s 900 native plant species are found in the Burren) and as a result it is also an important place for the pollinator diversity, especially bumblebees.

You can find several different bumblebee species including one in decline in Europe, the Shrill carder bee (Bombus sylvarum)which has its main Irish stronghold in the Burren. Some observations also notify the rarest Great yellow bumblebee’s presence (Bombus distinguendus). Both are late emerging species and endangered in Ireland.

Burren biodiversity is intimately linked to a traditional farming called « winterage », where livestock graze upland limestone grassland during the winter and move to lowland more fertile (but less diverse) grassland during the summer. This allows late summer wild flowers to grow up during summer and set seed, which also creates an incredibly diverse pantry for pollinators.

During the 1970’s, changes in agricultural management appeared in the Burren and elsewhere in Ireland supported by national and European schemes. The switch of traditional practices to conventional farming led to an increase in the earlier mowing of silage, grazing of limestone grassland during summer, or housing of livestock during winter. The diversity of late summer wildflowers specific to limestone grassland were reduced by grazing, or sometimes with scrub encroachement. As the result nesting habitats and forage resource for pollinators were also damaged, especially for the late emerging species.

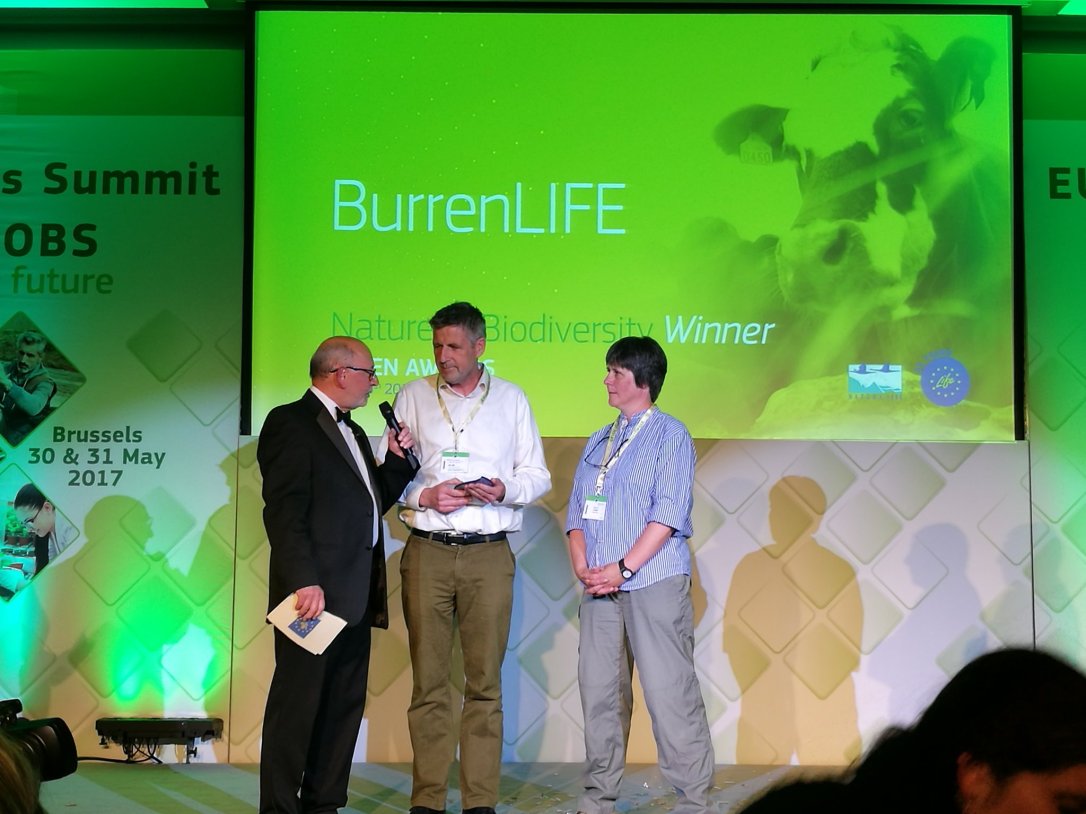

In 2005 the BurrenLIFE project was established to develop local practical solutions to the agricultural issues that threatened the priority habitats in the Burren. Mostly funded by the EU LIFE-Nature Programme, it was a partnership between the National Parks and Wildlife Service, Teagasc (the Agriculture and Food Development Authority) and the Burren Irish Farmers Association. The BurrenLIFE project was a result based agri-environment scheme, where farmers received payment for the ecological integrity of their land, among other factors, leading to environmental health turning into incomes per hectare for the farmer. Land with high health scores permitted to the farmer receive a high payment, whereas nothing was received if fields had a low (under 5) scores. Farmer also received payments for the improvement of water access and paths to grassland for the livestock to develop winter grazing. The project finished in 2010 with a great success (the project jointly won the EU “Best Nature” Green Award this year).

Currently the next phase of the project, Burren Programme (2016-2022), covers about 300 farmers across the Burren. The programme promotes floral diversity, and most likely by consequence safe habitats for pollinators. The ecosystem services for farmers improved also.

Traditional grazing methods increase wildflowers, and so improves the quality of habitats for pollinators. In turn wild pollinators enhance the quality of grassland, as they permit a better diversity and quantityof grazing for cattle food production and so enhance the quality of production. Burren Life Programme has been successful in maintening and promoting floral plant diversity characteristics to the Burren (You can read “Farming and the Burren” from Brendan Dunford for more information). Research is currently being carried out by Michelle Larkin (NUI Galway) to investigate whether this good management of farmland could have a positive effect on pollinator’s populations also.

Marie Carco is working with Trinity graduate and PhD holder Dr Dara Stanley (Lecturer in Plant Ecology at NUI Galway, @DaraStanley). Marie is in the first year of her Master’s in Biology, Ecology and Evolution at the University of Bordeaux.