Written by Dr Sarah Larragy, Postdoctoral researcher in Botany, School of Natural Sciences, Trinity College Dublin, working on the EU-funded RestPoll project, and Moya Owens, Research Assistant in Botany, School of Natural Sciences, Trinity College Dublin, working on the ANTENNA project.

As we trudge our way through the dark and grey wintertime, it is no wonder we are reminiscing over sunny, insect-filled days. The People and Nature group saw a very busy season last summer, which brought us to and from farms all around the Co. Kildare area to conduct pollinator research! Our travelling troupe of bug catchers this summer included:

• Dr Sarah Larragy (post-doc, RestPoll)

• Fernanda Azevedo (PhD student, RestPoll)

• Moya Owens (Research Assistant, ANTENNA)

• Michalis Cristou (Biodiversity and Conservation MSc student)

• Sarah Browne (Research Assistant)

• Katie Gahan (Research Assistant)

• Daan Mathijssen (Summer intern)

• Sirus Rasti (Erasmus plus student)

Figure 1 The TCD RestPoll fieldwork team (a lovely bunch 😊 – thanks for all your help!)

This work contributed to two pollinator-related EU projects being conducted by members of the lab:

• RestPoll: Restoring pollinator habitats across European agricultural landscapes (see Sarah’s blog here)

• ANTENNA: Making technology work for monitoring pollinators (see Moya’s blog here)

RestPoll field work

As part of RestPoll, we are collecting field data to see if restoration measures for pollinators are effective. Many of our farms were previously involved in Protecting Farmland Pollinators and carry out many practices that are likely to benefit our busy bees and other pollinators. These biodiversity friendly actions include reduced hedgerow cutting, reducing or eliminating insecticide use, increasing the area of field margins and letting ‘weeds’ grow in unfarmed areas.

To conduct our RestPoll field work, it was clear we were in for an intense season of insect counting (tough work but someone’s got to do it!). The traditional methods for surveying pollinators generally involve a transect walk – this is where one walks at a slow pace while keeping their eyes peeled for any bees, hoverflies or butterflies that pass through their path. Once we spot a pollinator, we note down the species and – should we spot them enjoying a floral treat – the plant species it visits. Over the summer, we conducted three rounds of pollinator transects and floral coverage surveys across 21 beef and tillage farms in the Co. Kildare region – and have the farmers’ tans to prove it!

Antenna field work

Overlapping with the RestPoll fieldwork was the much more technologically-advanced project, ANTENNA, conducted by Moya Owens (supervised by TCD alumni Dr Jessica Knapp, now based in Lund University!). Pollinator surveys have been conducted across 6 different countries in Europe, which included four rounds of surveys on five different sites in Co. Kildare.

ANTENNA is investigating the feasibility of using fancy, solar-powered cameras to conduct pollinator monitoring. It aims to compare these high-tech approaches to traditional methods, like transecting and pan trapping. While transects are the traditional and usually the core methodology for any pollinator monitoring project, there are limitations such as not being able to see, or identify, everything you spot in the field. Oftentimes, you need to catch an insect to find out what species it is, and sometimes this requires careful examination under microscopes. Also, insects can often be difficult to catch. You may not think it, but chasing a butterfly down in a field full of boisterous cattle or waist-high wheat is a surprisingly humbling experience. Indeed, Sarah L. faced an unusually specific conundrum one day when a cow made off with her butterfly net, presumably for its own scientific pursuits.

Other traditional methods, such as pan-trapping (multi-coloured buckets of soapy solution to catch insects) have the downfall of being a form of attractant, lethal sampling – an approach we are trying to reduce to mitigate negative effects on pollinator populations. Considering these limitations, technological approaches may be a solution to gathering much needed data on pollinator richness and abundance trends, as traditional methods are time-consuming and often require some level of lethal sampling.

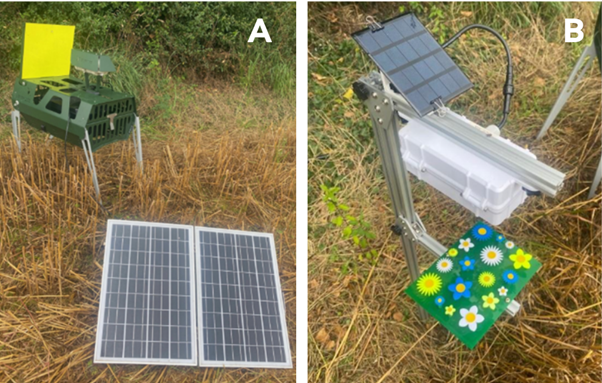

The cameras being tested in ANTENNA were a DIOPSIS 2.0 Insect Camera (Fig. 2A, Fig. 3) and a MiniMon camera (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2 Cameras being used in ANTENNA project include a DIOPSIS 2.0 Insect Camera (A) and a MiniMon camera (B).

The DIOPSIS camera is a fully automated system designed to detect, monitor and document insect populations, produced by Faunabit in The Netherlands. When an insect lands on the yellow screen, the camera captures high resolution images which are then uploaded to a server via Wi-Fi. Images are then processed using the image recognition model developed by Naturalis.

In terms of the MiniMon camera, this was developed by the ANTENNA team, with the aim of being a user-friendly, cost-effective camera. Unlike the DIOPSIS camera, which monitors continuously, the MiniMon camera takes a burst of five pictures every minute. As shown in Fig. 1, there is a custom-made flower plate containing 3-D printed artificial flowers which attract insects. As well as recording insects we found, we also took note of floral coverage around each stake (2m radius).

Figure 3 Katie, Sarah B. and Moya did trojan work bringing these cameras around to different sites to conduct 6-hour bouts of surveying! Here they are on day one of successfully setting up the DIOPSIS camera.

Fun finds

Over the course of the summer, we found some amazing insects, from painted lady butterflies (Vanessa cardui) to orange-tailed mining bees (Andrena haemorrhoa). Below we share with you our catches of the season!

Research Assistant Sarah B.’s main memories from this season include finding the Common Tiger hoverfly (Helophilus pendulus; Fig 4 A) and peacock butterfly (Aglais io). Another stand out moment from the summer was finding 5 small tortoise shell (Aglais urticae) butterflies on field scabious (Knautia arvensis). Katie Gahan, another Research Assistant working with us this summer, enjoyed the field full of common spotted orchids (Dactylorhiza fuchsii).

Figure 4 Some of our fun finds during field work season! A. Common tiger hoverfly (Helophilus pendulus). B. Common spotted orchid (Dactylorhiza fuchsia). C. The large carder bumblebee (Bombus muscorum). D. Many tortoiseshell butterflies (Aglais urticae) foraging on field scabius (Knautia arvensis). E. Peacock butterfly (Aglais io). F. A new buff-tailed bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) queen.

“My catch of the season was finally seeing a Large Carder Bee (Bombus muscorum) for the first time! I caught a male on one of the last days of surveying, which was even more exciting as it meant I got to hold him since males don’t sting! After I caught this one, we saw a couple more flying along the transect which was super exciting. This was probably the best day in the field for me!” – Moya

Figure 5 Moya only delighted with the male Bombus muscorum she found!

“My fun find is not exactly rare, but it is very beautiful – it is the buff-tailed bumblebee queen. In this picture we see a new queen who is likely preparing for her upcoming winter diapause by stocking up on nectar and pollen. I studied buff-tailed bumblebees during my PhD, so I always enjoy seeing these beautiful (and huge!) queens during such a vital part of their lifecycle. I also really loved seeing so many butterflies out after several mild seasons – a particular favourite was the painted lady butterfly (Fig. 6)” – Sarah L.

“I remember a day during our third round of surveys on Kepak farm where there were so many butterflies of different species out – it was really beautiful!” – Fernanda

Figure 6 A painted lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui).

A big thank you to the field work team for all their hard work this summer, it is so appreciated! And a sincere thank you to the farmers who let us come and count insects on their farms (and sometimes treated us to cups of tea!) – we couldn’t do this work without your support!