Written by Owen Small, researcher on the For-ES project in the School of Natural Sciences, Trinity College Dublin

Dramatisation of the headline aside, Natural Capital Accounting (NCA) is a trending framework for ascribing value to ecosystems, that – in the eyes of this particular researcher – has a wide disparity in the potential outcomes it may lead to.

On one hand, we have a means to reshape our current economic systems in a manner that prioritises nature like the essential driving force of life it is. On the other, we have a streamlined methodology for powerful private interests to further commodify the natural world, widening existing wealth gaps and propagating the exploitation of developing countries. Standing at this crossroads, the scientists, economists, conservationists and humanists that recognise the powerful tool NCA might be, must face it for what it could be bastardised into.

“Concern for man himself and his fate must always constitute the chief objective of all technological endeavors… in order that the creations of our mind shall be a blessing and not a curse to mankind. Never forget this in the midst of your diagrams and equations.”

– Albert Einstein.

Einstein uttered these words at a speech at the California Institute of Technology on 16 February 1931. Despite Einstein’s words, there still sometimes seems to exist a lack of consideration for externalities during the rigors of research. It’s of course a folly of a system that demands constant advancement and output, otherwise experts face redundancy, but still a flaw in the process none the less. The point I’m overexplaining is we must move cautiously and deliberately with frameworks connecting the living, natural world to monetary values.

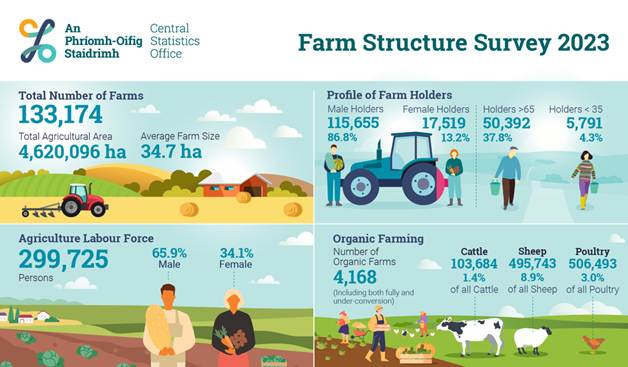

Three paragraphs in, perhaps it’s a decent time to define NCA, and the specific ecological-based aspects I’m referring to. Natural capital is simply all that comes from nature; soil, water, animals, plants, etc. The accounting bit refers to measuring the change in extent and condition of this natural capital, the stock as it’s called. In a more particular context, we have ‘Ecosystem Accounting’ which measures and tracks this stock over time, as well as how humans use it, or the flow of ‘ecosystem services.’ These services again are how humans use the ecosystems they exist in or adjacent to. Generally, they’re divided into four types: provisioning (food, timber), regulating (flood control, carbon sequestration), cultural (recreation areas, sacred sites), and supporting (photosynthesis, the water cycle). Fundamentally, human life and society do not exist without ecosystem services.

Figure from SEEA EA, conceptualising Ecosystem Accounting

At face value, this all sounds great. A system that seeks to monitor and track where ecosystems are, how they’re doing, and what they provide us. The issue lies not in the means or purported ends, but the potential perversion of its goals. Under the System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA), there is an intention to reach a level where monetary values are calculated for ecosystem services and stock, albeit these monetary valuations are not ratified by the UN. The SEEA Implementation Strategy explicitly mentions intended uses for ecosystem accounting (EA) being to drive private and public investment for nature restoration, inform policy, and support current reporting requirements.

Figures from Mascolo et al. (2025) showing Natural Capital Accounts for Italy in 2021. (left) Net carbon sequestered by ecosystems. (right) Wood provisioning provided by forested areas.

This all sounds excellent, and there have been successful pilot projects and ongoing uses of SEEA EA. At a national scale in Italy, spatially explicit valuation of ecosystem services has improved the allocation of EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) subsidies, directing restoration funding to areas indicated for high returns (European Union, 2024; Mascolo et al., 2025). A multi-national SEEA EA pilot initiative helped quantify where forest degradation was avoided in Central and South America, as well as Southeast Asia, and even saw reform of forest repayment schemes in Mexico through the Natural Capital Accounting and Valuation of Ecosystem Services Project (NCAVES) (United Nations Statistics Division & United Nations Environment Programme, n.d.). Some studies even claim that the principles of NCA adopted in green accounting with private corporations have demonstrated improved financial performance (Tjandrakirana et al., 2024). It’s that last example, however, where the cause for concern can arise.

Accusations of politicising a discussion can be brought up when critiques of capitalism, and its impacts on the environment, are contended. Personally – as an independent individual whose views are my own and not any group or institution’s – I see enough categorical and empirical evidence supporting the statement that traditional capitalist systems, and the inherent growth dependency and profit maximization, are contradictory to current climate and biodiversity goals. While it’s encouraging to see organisations willfully partaking in more sustainable practices, it begs the question of whether these goals and practices are maintainable for profit-driven sectors.

Now, credit where credit’s due, that is in a sense the point of NCA and ecosystem accounting. Realign the priorities of financial systems so that profit is not the sole goal, but overall environmental health and human equity is an aim. In a vacuum, monetary systems are not destructive to ecology. Just as there’s exchanges of energy in a rich and dynamic trophic web, humans exchange currency in equally complex economies. That said, I’d safely assume most researchers in the field of NCA would all agree that the relationship between humanity, our economy, and nature needs to be overhauled in order to meet critical ecological goals. Where my previous sentiment was drawing alarms are the various stakeholders that would not view ecosystem accounting as means to change a system, but rather to further perpetuate their own economic power.

Image of common ‘Greenwashing’ terms from How to tell if a company is greenwashing – spunout

‘Greenwashing’ as it’s called is the new buzzword that really captures where a lot of my worries would lie. Thanks in part to ineffectual policy, or enforcement of existing legislation, countless companies in the developed world sell products labelled as “green” or “sustainable” with no true data to support it. Often the products are actually significantly damaging the environment. The easiest example, which the veil has been pulled back a little, is plastics and recycling. It’s very well documented that only a fraction of plastic products are truly recycled, and even the process of recycling them has its impacts, yet many companies still push “100% recyclable container” or “packaged made of 50% recycled plastic.” It’s predatory marketing practices harvesting a premium from environmentally conscious consumers.

Lets imagine greenwashing, but on a systemic scale rather than just the marketing and retail level. Weaponising NCA methods, companies whose industrial practice, regardless of any adjustments they can make, damage the environment (fossil fuels, strip-mining) could use ecosystem accounting to minimise and mask their impacts. One objective critique of NCA is, while there are standards in place, the operationalising of SEEA EA is largely site/stakeholder dependent. Accounts must be developed with goals in mind and vary region by region. Now, if a fossil-fuel company wipes out a protected habitat, there is not much data manipulation to be done to mask that, but what could be done is active minimisation of the wider impact. Ensuring condition and ecosystem service accounts downplay what this ecosystem provided, and perhaps even upscaling what other land the company may own has.

Yes, I’m jumping several steps ahead and making very large and brash assumptions, but that was precisely my point with the Einstein quote. His work, however indirect, contributed to the atomic bomb, and he even signed a letter with others warning the U.S. government of Germany’s atomic potential, a decision he would later voice regrets on learning more about how far they were. Despite that, America’s advancements in the 1930s/40s led the world to a nuclear era with unforeseen risks and consequences. Could physicists have treaded more carefully and brought us instead into an age of safe, nuclear energy? Similar questions, not quite as heavy questions could be asked when developing valuations for ecosystems. How do we, as NCA researchers, avoid a similar mistake and prevent for-profit private enterprises from misusing the principles of ecosystem accounting?

I’ve worked in the field for less than a year, so obviously have no answers myself. Moreover, there are countless distinguished experts in the NCA landscape who have had these same worries and asked the same questions. This is just the outward reflections of someone that has dove in and been inundated with a fascinating new perspective on quantifying and understanding humanity and our relationship with nature. Frankly, I worry it is too anthropocentric, plain and simple. It takes something that should be inherent, care for nature, and frames it in a transactional manner: nature good = humans good. If used as intended and responsibly, could NCA still contribute to our separation from nature? We frame it as capital – nature is an asset. I disagree; nature is us. We are innately part of the formula, not one side of an equation: nature good + humans good = Earth good.

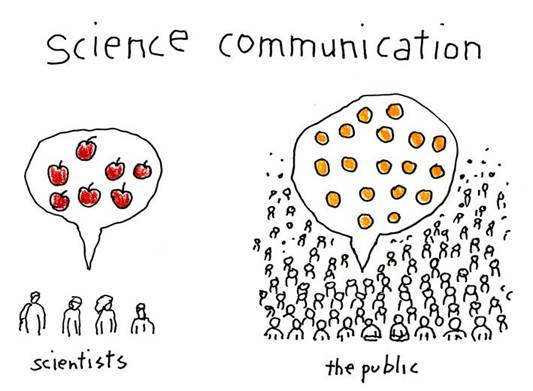

Science Communication cartoon by Tom Dunne

But, as a realist rather than idealist, ecosystem accounting is a practical solution regarding an already degraded relationship. Perhaps as it becomes mainstream, develops and improves, that inherent sense of caring for nature will be restored. In many ways, natural capital serves to speak on protecting biodiversity and improving sustainability in terms the people with significant impact understand. It’s the language of policymakers that fret about GDP, and the vernacular of corporations that cause the larger scale impacts. An ecologist’s understanding of something means little if it can’t be communicated to people making decisions. Creating ecosystem accounts is a form of communicating info many experts already know. On a macro-scale, it’s “laymen’s terms” for describing ecosystems, how they’re doing, and how important they are.

As we continue advancing Natural Capital Accounting, especially those of us developing new methods to quantify ecosystem services and their valuations, the responsibility is not abstract. I work on experimental recreation-related services accounts using relatively novel methods and a dataset with inherent bias. They offer an interesting perspective into understanding how people feel about and use an ecosystem. In the wrong hands, the accounts could easily be used to misrepresent the true sentiment of a community for a natural area. That’s a powerful tool that should be handled properly.

“The creations of our mind shall be a blessing and not a curse to mankind,” Einstein said. It’s not the ecosystem accounts alone that determine which contrivance of humanity it shall be; it’s the structures and systems that use it that decide. We can communicate nature as an asset but must make it clear that nature’s value is irrespective of its ability to serve people. Nature is valuable to humans. When we restore those last two words, we turn our relationship with nature into a transaction.

A photo of something ‘valuable’, from a walk in Co. Wicklow, Ireland

References

European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/3024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2024 amending Regulation (EU) No 691/2011 as regards introducing new environmental economic account modules (SEEA EA). Official Journal of the European Union, L 3024. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/3024/oj/

Mascolo, R. A., et al. (2025). Towards National Ecosystem Accounts: A First Application of EU Regulation 2024/3024 in Italy. One Ecosystem. https://oneecosystem.pensoft.net/article/161992/

United Nations Statistics Division & United Nations Environment Programme. (n.d.). Natural Capital Accounting and Valuation of Ecosystem Services Project (NCAVES). SEEA UN Project Portal. https://seea.un.org/home/Natural-Capital-Accounting-Project

Tjandrakirana, R. D. P., Ermadiani, E., & Aspahani, A. (2024). The impact of environmental performance, green accounting, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) on financial performance. International Journal of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences (IJHESS), 4(3). https://doi.org/10.55227/ijhess.v4i3.1335